Target Date Funds and Stock Market Dynamics

In response to stock market moves, target date funds rebalance their portfolios to achieve a preset mix of stocks and bonds, thereby creating a force that may dampen market swings.

Retail investors who hold mutual funds often chase performance, investing more in funds that outperform their counterparts and in stock funds in general after periods of strong stock market returns. Target date funds (TDFs), in contrast, follow a rigid rule for the share of their assets that is invested in stocks and bonds. When stocks rise, these funds must liquidate part of their equity position to restore their stock-bond balance. In contrast to some investors’ trend-following behavior, these funds display just the opposite dynamic. The rapid growth of TDFs may therefore be exerting a mean-reverting pressure on equity prices.

In Retail Financial Innovation and Stock Market Dynamics: The Case of Target Date Funds (NBER Working Paper 28028), Jonathan A. Parker, Antoinette Schoar, and Yang Sun find that following a stock market rise of 10 percent in one quarter, the typical equity mutual fund sees an extra inflow of about 2.5 percent of its asset holdings. This inflow is smaller, however, only about 2 percent, for equity funds that are partly owned by TDFs.

TDFs allocate a fixed percentage of their investors’ money to stocks and bonds, typically investing through stock and bond mutual funds. The mix is determined by the approximate retirement date of the investors for whom the fund is designed. TDFs marketed to young investors, such as a “target date 2060 fund,” adopt an investment mix that is heavily tilted toward equities, often with 80 to 90 percent of their assets in stock funds and the rest allocated to bond funds. As years pass and the target date of retirement draws nearer, the fund manager slowly decreases the TDF’s share in equities to reduce the risk of a sharp drop in the fund’s market value as the investors approach retirement. By a decade after the fund’s target date, when the intended investors are well into retirement, the average TDF has between 30 and 40 percent of its portfolio in stocks.

As a result, after large movements in either bond or stock prices, different TDFs should rebalance their portfolios by different amounts depending on their desired mix of stocks and bonds. And indeed they behave as predicted. From 2008 to 2018, in quarters when stock funds outperformed bond funds, the average TDF sold equity funds and bought bond funds. For every dollar of excess return on the stock market in a quarter, the typical fund sold stocks and bought bonds to bring its balance of stocks and bonds halfway back to its desired mix in the same quarter. In the following quarter, the TDFs trade to eliminate almost all the remaining gap.

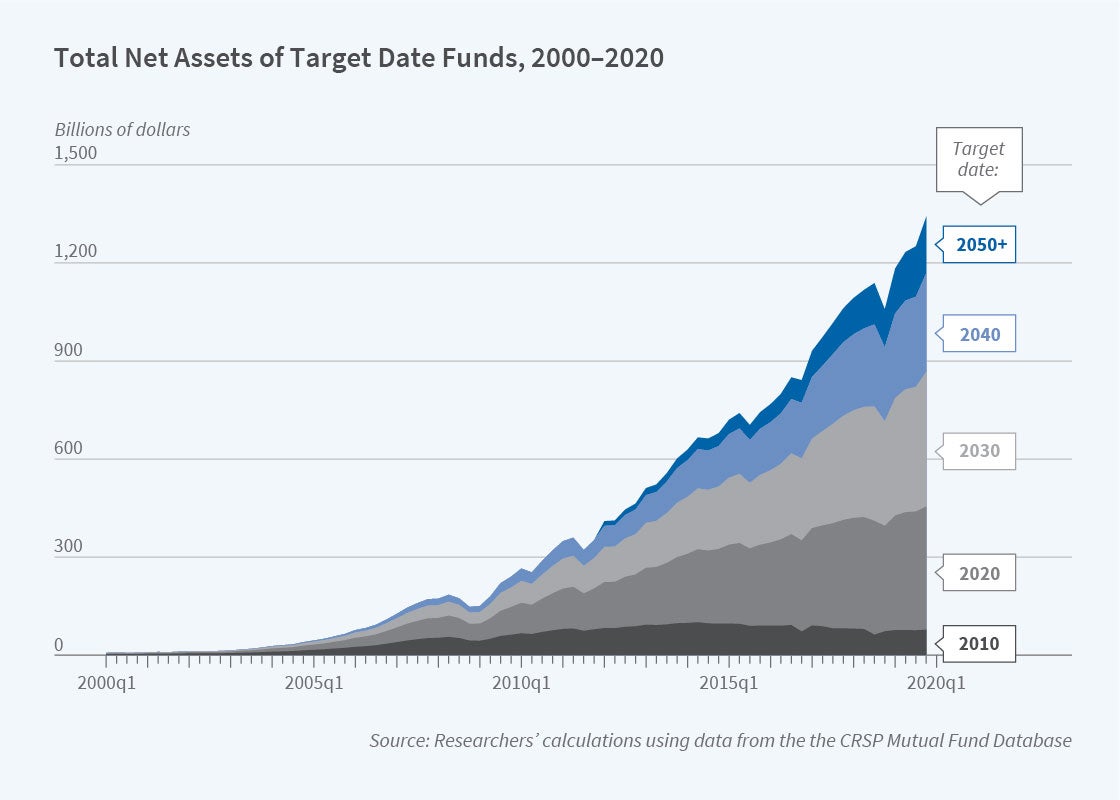

The impact of TDFs on market dynamics has grown with the popularity of these funds. In 2000, less than $8 billion was under TDF management; by 2019, there was over $2.3 trillion, slightly more than 10 percent of the roughly $21 trillion mutual fund market.

The researchers find that individual stocks that have high TDF exposure through mutual funds tend to have lower returns in the quarter after they outperform the market. When the stock market goes up by 10 percent in a quarter, an increase of 0.6 percent (one standard deviation) in the fraction of a stock that is held by TDFs is associated with a decrease of 0.24 percent in that stock’s return in the next quarter. This appears to be due to the behavior of TDFs, not to their selection of stocks. Stocks that are included in the S&P 500 have a higher share of TDF ownership than similar stocks that are not part of that index, and they exhibit above-average mean reversion in their price movements. The researchers speculate that the rise of TDFs not only affects the returns on individual stocks, but may also impact the stock market as a whole.

— Laurent Belsie